One of the key “secrets” of the Marlboro Festival experience is the time one has here to study, practice, and rehearse in a way that is not possible at other times and places.

Over the last few weeks, in preparing for rehearsals with colleagues here on a “standard” piece I’ve performed several times over the years—Beethoven’s Piano Trio in C minor, Op. 1, No. 3—I became frustrated, for the nth time, with the ambiguous or insufficient markings left to us from the original editions (the autograph being lost). There are so many questions, and no way to know what Beethoven was thinking, or why there exist so many unresolved ambiguities.

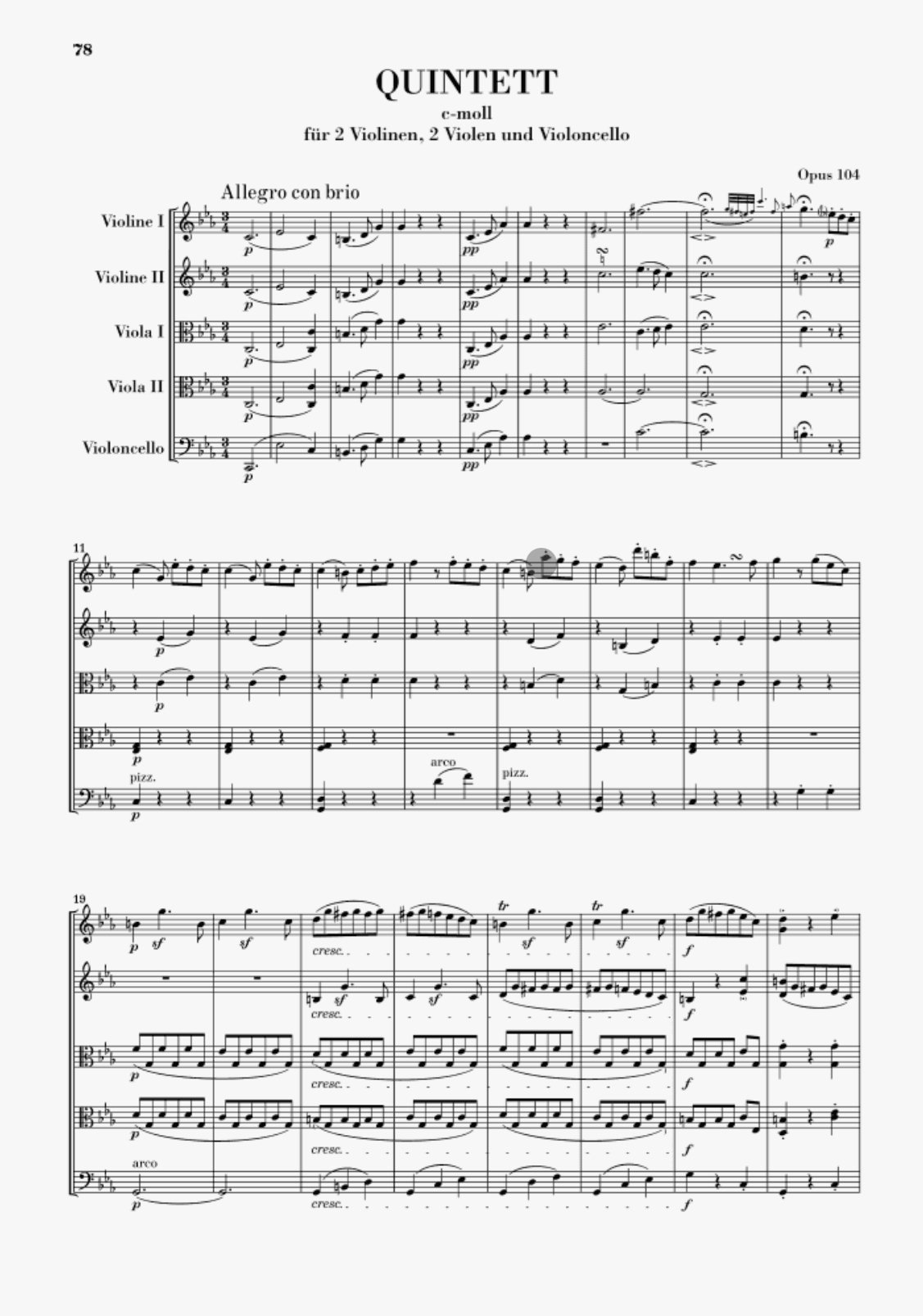

No way to know… except that, a quarter of a century later, Beethoven returned to this work, re-imagining it as a string quintet, published in 1819 as Op. 104. What is remarkable about this transcription—apart from its inherent richness and freedom—is how carefully the Master hews to his model while never missing an opportunity to clarify, re-think, flesh out details of phrasing, dynamics, and articulation.

Let me share an instructive example right on the first page. Consider the thrilling phrase that begins in Bar 19—is it piano? is it forte? are the sforzandi in the piano and violin parts “static”, or do they indicate growth? what is that lone, long hairpin doing in the cello part, and is it only there because, even on Beethoven’s instruments, the cello was disadvantaged and needs to grow here to be heard in good balance?…

All very problematic and open-ended and more questions are raised than answered… but now look at the quintet version:

At the beginning of the phrase, in Bar 19, all instruments are clearly marked piano. There is a general crescendo that begins in 21, marked in every part and with Beethoven’s patented continuation marks to boot, themselves leading in the clearest way to a general forte in 25.

What a relief to understand exactly how Beethoven wants this phrase to go. But the follow-up question immediately arises: does this revision/reimagination trump the original version? or should they be treated as separate entities, allowing that Beethoven simply saw things differently all those years later?

For me, the best answer is to decide on a case-by-case basis: where something truly different seems to be intended, vive la différence and let each stand on its own; but where—as here—a later revision is obviously intended to clarify/refine notation that was ambiguous or sloppy in the first place, by all means learn from the later improvement and import it back into the original, in the reverent hope that LvB would heartily approve.